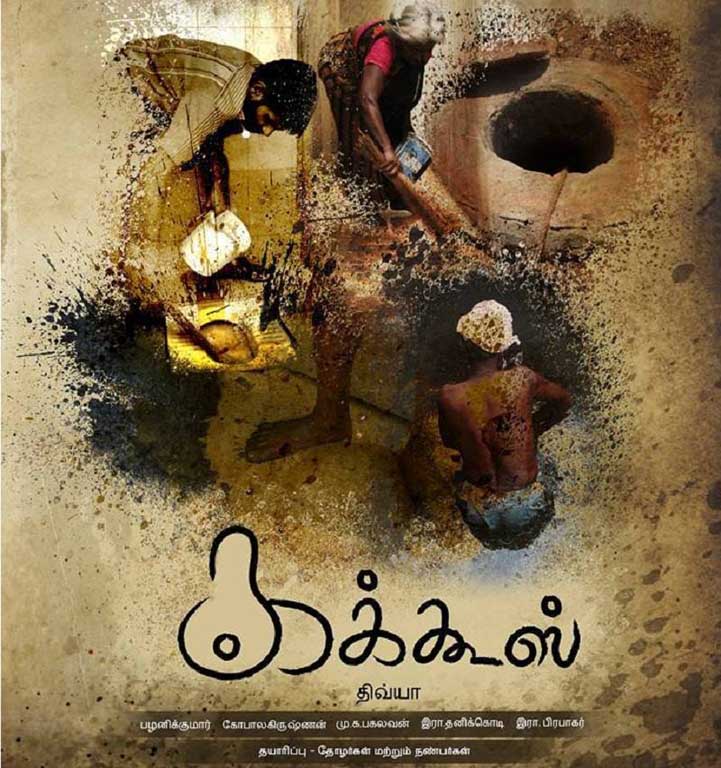

(The Cinema Of Resistance brought the documentary film Kakkoos and its filmmaker, the young Divya Bharathi, to Rajasthan, Delhi and Bihar. Liberation reports on one of the screenings of the film took place in the CPI(ML) Liberation central office, followed by a discussion with Divya.)

‘Kakkoos’ means ‘toilet’ in Tamil. The film Kakkoos is a difficult one to watch. It brought several of its viewers to tears – because of the relentless way in which the film forces the viewer to confront the inhuman degradation and oppression to which manual scavengers are submitted, thanks to having been born into Dalit communities.

Sanjay Joshi of Cinema of Resistance introduced the film and Divya to the audience. The film calls the bluff of a ‘Swacch Bharat’ campaign that ignores the conditions of sanitation workers. It exposes the continuing reality of manual scavenging in Tamil Nadu where the Government claims to have eradicated manual scavenging.

In frame after frame, the film introduces us to the men and women who clean cities and towns: how they are made to clean human excreta, used sanitary napkins, rotting bodies of animals, corpses of homeless people, drains and sewers, mountains of trash full of potentially dangerous materials – without so much as a pair of gloves or a broom, let alone any other more sophisticated equipment. They speak of how society treats them as if they – the ones who clean the dirt of others – are the ‘dirty’ ones. They are not served water in glasses or tea in cups – untouchability is alive and well. The anger and pain in their voices and faces haunts the viewers forever afterwards – forcing us to examine our own complicity with and willful blindness to this ugly, brutal reality.

The film asks the question most asked by privileged and unthinkingly insensitive people: ‘why don’t these people do some other work instead?’ This question is much like Marie Antoinette’s ‘Let them eat cake’. The workers speak of how they will be given no other work, because of their caste status. Women speak of how, even when they are employed as sweepers in a school, they will be asked to clean toilets and even clean the bottoms of school children. The horror of it is that workers who are laid off the job immolate themselves out of despair and frustration – because it’s their only means of survival. Children from these communities are deterred from going to school because schools often ask them to clean toilets, and demoralize them by telling them that education is not for the likes of them.

The film asks the question most asked by privileged and unthinkingly insensitive people: ‘why don’t these people do some other work instead?’ This question is much like Marie Antoinette’s ‘Let them eat cake’. The workers speak of how they will be given no other work, because of their caste status. Women speak of how, even when they are employed as sweepers in a school, they will be asked to clean toilets and even clean the bottoms of school children. The horror of it is that workers who are laid off the job immolate themselves out of despair and frustration – because it’s their only means of survival. Children from these communities are deterred from going to school because schools often ask them to clean toilets, and demoralize them by telling them that education is not for the likes of them.

The film shows how privatization and contractualisation of sanitation services has made matters much worse for the workers, who are now paid a pittance and at risk of dismissal at the slightest sign of protest. Contractualisation also allows the Government to pretend it has nothing to do with sewer deaths or inhuman practices of sending workers into sewers to clean them. How does the Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CMWSSB) recruit contract sanitation workers? The film documents how young men from Dalit communities line up and are asked to strip down to just a loin cloth, drink alcohol, and are then sent into a sewage hole holding a rope. Those outside the hole count off seconds – the men who can hold their breath for 3-4 minutes are selected! Could there be a Government agency in any other country of the world that recruits workers like this?

A large section of the sanitation workers are women. They speak of how disposing of soiled sanitary napkins reeking of old menstrual blood is not recognized as manual scavenging by the 2013 law outlawing manual scavenging. And the tears and anger of the women whose husband, father, or son has died while cleaning sewers are an indictment of the society we live in. Along with workers from Tamilnadu itself, migrant workers are also recruited as contract sanitation workers. The film shows the death of a migrant labourer from Bihar inside a sewer. The film documents how the Tamilnadu municipal corporations fake the numbers of manual scavengers.

A musical team sings a song that asks the world, “Are you there to shit, tell us, and we to clean?/Are you there to rule, we to die?”

In the conversation that followed, Divya spoke about how the Dalit organizations tend to focus on issues of caste discrimination and dignity, and ignore issues like wages, privatization and contractualisation; while the Left trade unions while raising the latter issues tend to place less emphasis on the former. She felt that there was an urgent need for unity and for raising issues of sanitation workers – as Dalits, as workers, as women, together. In response to a question she pointed out that the fragmentation of Dalit politics into parties based on specific castes was also a hurdle to raising the question of annihilation of caste and of eradicating manual scavenging as political issues.

Divya was asked about how sanitation workers in Bengaluru and Karnataka, organized as AICCTU, reacted to her film. She said that sanitation workers always break down while viewing the film, and stop the screening saying they do not need to see the work they do everyday – the film is to wake others to the inhumanity. Instead sanitation workers want to talk about their struggles. She said that the Bengaluru Guttige Powrakarmikas (Contract Sanitation Workers) struggle is truly a model one that inspires their sisters in other states, because here they have successfully won a significant raise in minimum wages, and also powerfully raise the issues of their dignity as Dalits.

Divya spoke about her journey into film-making. A daughter of a cotton mill worker, she was introduced to film at the age of 14 by CPI(ML) cultural activists who would screen world cinema to school kids in her area. She was soon drawn into the communist movement as well. When she began to study Visual Communication, she stayed at the CPI(ML) party office. She was a leading activist of AISA, and led struggles against dangerous conditions in Dalit students’ hostels in Madurai. Due to heavy fines during an agitation she was forced to discontinue her film studies.