An obituary often mourns and bids adieu. This one will not. Type Dario Fo’s name on any search engine and you will see image after image of this happy looking man with round eyes, on stage and off, laughing, hugging, dancing. It is only in politically minded celebration during and despite dark times that you can remember Dario Fo, for his legacy of humour is an incredibly durable and endearing template for our times.

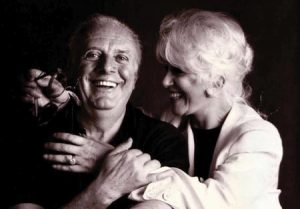

When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1997, as he notes in his acceptance speech, many friends of his said that the Swedish Academy should be applauded ‘for having had the courage to award the Nobel Prize to a jester!’ Dario Fo was no writer who toiled away through the nights to the tap of the typewriter in glum literary solitude. He had no solemnity becoming of a literary figure whatsoever. In fact, in the same speech, in describing those men of letters who were stumped at his winning the prize, he says, “It’s enough to take stock of the uproar it has caused: sublime poets and writers who normally occupy the loftiest of spheres, and who rarely take interest in those who live and toil on humbler planes, are suddenly bowled over by some kind of whirlwind.” Fo was that whirlwind of the stage, a wind that lit political fires, by telling the stories of the humble and the toiling. He was the most complete being of the theatre, who wrote plays and directed them, who acted in them and made music for them. And this he did with his friend, love, partner-in-laughter, wife, Franca Rame, with whom he toured with their bagful of stories in performance, and who he said deserved the prize along with him. The Swedish Academy rightly said that in giving the award to Fo, they had honoured someone “who emulates the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden.”

When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1997, as he notes in his acceptance speech, many friends of his said that the Swedish Academy should be applauded ‘for having had the courage to award the Nobel Prize to a jester!’ Dario Fo was no writer who toiled away through the nights to the tap of the typewriter in glum literary solitude. He had no solemnity becoming of a literary figure whatsoever. In fact, in the same speech, in describing those men of letters who were stumped at his winning the prize, he says, “It’s enough to take stock of the uproar it has caused: sublime poets and writers who normally occupy the loftiest of spheres, and who rarely take interest in those who live and toil on humbler planes, are suddenly bowled over by some kind of whirlwind.” Fo was that whirlwind of the stage, a wind that lit political fires, by telling the stories of the humble and the toiling. He was the most complete being of the theatre, who wrote plays and directed them, who acted in them and made music for them. And this he did with his friend, love, partner-in-laughter, wife, Franca Rame, with whom he toured with their bagful of stories in performance, and who he said deserved the prize along with him. The Swedish Academy rightly said that in giving the award to Fo, they had honoured someone “who emulates the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden.”

Born in 1926 in Sangiano, Italy, little Dario sat beside his grandfather who sold farm produce out of a cart, and told the most fantastic stories. His father Felice was a socialist and committed anti-fascist, and his job as station master took the family across the country, where Dario listened to more fantastic stories from fishermen and glassblowers, even as his mother wrote reminiscences of post war experiences in Italy. He rightly deserted the army, went to study architecture in Milan, and gave up the soullessness of architecture to throw himself into the little theatre movement that in the post war years was growing and throbbing with social critique.

Fo’s wild satirical humour discomfited the establishment right when he first opened his mouth to a public, in the early 1950s, when he did 18 comic monologues in a series called Poor Dwarf (Poer Nano), in which he stood biblical, historical, and Shakespearean tales on their heads, and angry radio authorities cancelled the show. Having devoured works by Brecht, Gramsci, and Marx as a young man, Fo was not to be reined in by these interruptions. Along with Rame, he continued depicting the lives of the working classes, the endless injustices faced by them, always in satirical hilarity, resulting in the couple being effectively banned from Italian television for over a decade. He went on to take on another sacred cow of European history – the thug Chris Columbus, whom Fo demystified in the play Isabella, Three Sailing Ships and a Conman, in which he debunked the text book version of Columbus as the great explorer. This led to threats and attacks by the fascists. Unabated, the couple then took on the US establishment – having earlier also staged a play on racism in the US – in Throw the Lady Out, in which the ‘lady’ was interpreted by one critic as American capitalism. The US government continued denying him and Rame visas, not just for the play, but for their support for families of left-wing militants in Italy.

In 1969, he began staging Mistero Buffo (Comical Mystery Play), which took on various stories of the passion of Christ and retold them through the eyes of the common person, brought satire, erudition, and laughter to cast a big beady eye on politics of the time. Of course, telling tall tales about Jesus and other biblical characters had the Vatican hot around the clerical collar. But the audiences loved his one man show and the act toured the world for the next thirty years.

Fo is known also for the unforgettable Accidental Death of an Anarchist, produced by Rame and Fo’s independent theatre group in 1970, which took on disturbing concerns of his time: the death of the anarchist and railway worker Giuseppe Pinelli, who was picked up following a bomb explosion in a Milanese square caused by a far right group. In the cover up, the police made his death from a fall from the fourth floor of the police station look like an accident. The sharp commentary on police corruption, persecution of those whose politics resonated with Pinelli’s, were universal experiences that endured in many translations, adaptations, and performances across the world, including in Hindi and Kashmiri.

Taking on the political establishment and the far right had its dark shadow. In 1973, Rame was picked up at gunpoint by five fascists supported by the police, and raped, brutalised, and left in a park. Yet, the couple continued touring the country with their political satire, going on to tell the story of Salvador Allende and the struggle of the people of Chile, and in a few years that of the economic crisis closer home in Cant Pay? Won’t Pay!, in which a housewife, played by Rame loots supermarkets because she has no money to pay. Played always to packed houses, the play, again, was translated and adapted and the whole world adopted it and laughed with it. After all, the working class woman all over the world still can’t pay for groceries, can she?

Indefatigably, despite attempts to muzzle him and arrest him, and create all kinds of obstacles when he and his theatre company occupied an abandoned building in a working class district in Milan, Fo continued to thematise the elections, the class nature of the drug problem in Italy, a TV show called Let’s Talk about Women, in which they thematised burning issues around women’s rights at the time. In the middle of all that, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize, and kept laughing at the prospect of seeing the look on the Italian establishment’s face should the prospect come true. In the 1980s, while Fo’s plays were being widely performed across the United States, the US government mulishly continued denying the couple visas, mystifyingly declaring the reason that they were associated with terrorist groups, this being their association with the radical left in Italy. The couple simply filed a lawsuit against the US State Department!

And when Fo and Rame returned to Italian television, they again were the storm of jibing laughter with their critique of the banking establishment, rape culture, and state censorship.

Always the internationalist, having spoken out against the Vietnam War, Fo now took on the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Gulf War, AIDS, genetic experiments, and closer home kept making fun of the church and of Silvio Berlusconi. In The Two-Headed Anomaly, first performed in 2003, Fo presents the comic madness of a scenario where Vladimir Putin is shot dead and his brain transplanted into Berlusconi’s head – a comment on Berlusconi’s businesses and control of the media. And of course, Fo took all the threats that followed in his jaunty stride. Always the hero of the left, through his association with the Italian Communist Party (PCI), Fo later championed the cause of the Five Star Movement, led by Beppe Grillo.

In 2013, Franca Rame, his artistic collaborator, critic, muse, and comrade for nearly six decades, died. Years earlier, in his Nobel lecture, he had summed up their shared political values and their lives together thus: “Together we’ve staged and recited thousands of performances, in theatres, occupied factories, at university sit-ins, even in deconsecrated churches, in prisons and city parks, in sunshine and pouring rain, always together. We’ve had to endure abuse, assaults by the police, insults from the right-thinking, and violence. And it is Franca who has had to suffer the most atrocious aggression. She has had to pay more dearly than any one of us, with her neck and limb in the balance, for the solidarity with the humble and the beaten that has been our premise”.

He decided that the best tribute to her was to continue his creative endeavours, which were not fun and games, but were a radical, zestful, and perhaps optimistic reworking of Italian aesthetic traditions. Fo continued to paint, write, and speak, even writing a novel on the controversial Lucrezia Borgia, the daughter of Pope Alexander VI, recasting her as a modern woman, and the machinations of her infamous family as bearing parallels in modern life and politics.

And in all this, he continued to make fun of a decrepit and corrupt political establishment. It is only fitting that Umberto Eco, who in his own dazzling writing fantasised about the lost second book of Aristotle’s Poetics that is said to have talked of the theory of comedy and laughter, delighted in Fo receiving the Nobel Prize. To quote the inimitable jester again, who recalled Molière and Ruzzante Beolco as inspirations: “both actors-playwrights, both mocked by the leading men of letters of their times. Above all, they were despised for bringing onto the stage the everyday life, joys and desperation of the common people; the hypocrisy and the arrogance of the high and mighty; and the incessant injustice. And their major, unforgivable fault was this: in telling these things, they made people laugh. Laughter does not please the mighty”.

In that historical moment when there seems to be a ruling consensus on the inevitability of capitalism, we need to use the little stiletto of humour to stab that consensus, and to expose its dark soul. And that is why, in remembering him, in keeping our own beady eye on the powerful and the corrupt, we have to learn to laugh with and for the little people in history.