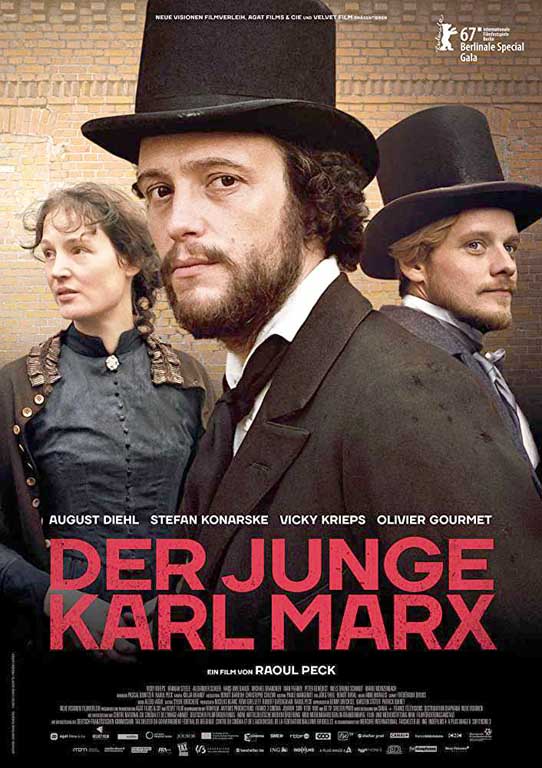

(Liberation carries excerpts of two reviews of an exciting new film – The Young Karl Marx – that was screened recently at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI).)

A Rivetting Film

Daphna Whitmore

This movie is two hours of non-stop Marxist banter. Tossing around the ideas of Marx, Engels, Proudon, Bakunin and Weitling, with references to Hegel here and there, it should be as dry as hell, even for a hardened Marxist. It’s not. It is rivetting. At the Auckland International Film Festival the audience stayed and applauded as the credits rolled.

This movie is two hours of non-stop Marxist banter. Tossing around the ideas of Marx, Engels, Proudon, Bakunin and Weitling, with references to Hegel here and there, it should be as dry as hell, even for a hardened Marxist. It’s not. It is rivetting. At the Auckland International Film Festival the audience stayed and applauded as the credits rolled.

The opening scene has destitute folk collecting firewood in a forest, and moments later they are savagely beaten by police on horseback. Marx contemplates how gathering dry wood, fallen from the trees and destined to rot on the forest floor, can be treated as an act of property theft?

Directed by Raoul Peck this movie is overtly sympathetic to Marx. Peck tells the story straight: Europe is seething on the brink of revolution and radical ideas are forming in tandem.

Based on letters between Marx and Engels in the 1840s the bond between these two revolutionaries is a central theme of the movie. Engels’ research on the condition of workers in England had caught Marx’s attention. Engels was already in awe of Marx’s brilliance and urging him to work on an economic analysis of capitalism.

The acting is good, and August Diehl plays a convincing Marx. He, along with Vicky Krieps (as Jenny Marx) and Stefan Konarske (as Engels) are fluent in German, French and English which packs a load of authenticity.

The women characters are not appendages in the movie, and rightly so. Mary Burns, a militant worker, played by Hannah Steele, is Engels’ de facto wife. Her Irish working class connections provide Engels close insights into working class life. The dire poverty that Marx and his wife endure, and Engels’ angst over the need to maintain his capitalist income adds to the human story along with the historical dramas unfolding. The film culminates with the writing of the Communist Manifesto.

The 1840s were a big decade and more than enough for one movie to chew on.

The end is a short montage of scenes from Che Guevara, Vietnam war protests, the Berlin wall coming down, Thatcher and Reagan, and more recent protests, perhaps reminding us the philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is to change it.

(Courtesy Redline)

Exploits of a Fabulous Trio

Peter Schwarz

The Haitian-born director Raoul Peck has set himself the task of presenting the formative years of Marxism in a film. He is well aware of the timeliness of his theme. “At a time when the world is in a state of emergency due to the financial crisis, Karl Marx is experiencing unexpected interest,” he writes in a contribution to the film. More than 25 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was now possible “to return to Karl Marx’s contribution to science without feelings of guilt.” The task of the film, he explained, is “to discover the real contribution of this scientific and political thinker.”

The Young Karl Marx focuses on a strictly limited period. It begins with the prohibition, in March 1843, of the Rheinische Zeitung, which Marx led as editor, and concludes with the writing of the Communist Manifesto at the end of 1847. These are the years during which Marx and Engels broke with the petty bourgeois democrats and laid the theoretical foundations for the modern, socialist workers movement.

Peck, who became acquainted with Marxism as a student in the West Berlin of the 1970s, refrains from any attempt to construct a contrast between the “romantic” and “covert idealist” Marx and the materialist Engels, as was usual among “Western Marxist” circles of the time. The film repeatedly identifies Marx as a “great materialist” and expounds the revolutionary basis of the friendship between Marx and Engels: their determination not to reconcile themselves with the existing conditions of exploitation and the half-heartedness of the petty-bourgeois democrats.

One of the main focal points of the film is Engels’ experience in England with his father’s textile business in Manchester—where Engels works as a clerk—and the terrible living quarters of the working class. Engels could access the workers’ quarters, thanks to his girlfriend Mary Burns—but not without receiving a bloody nose in the process. Here he assembles the material for his book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, which appears in 1845.

The film shows quite correctly that it was Engels who pointed out to Marx the importance of the writings of the classical English economists. His article, “Outline of a Critique of National Economy,” published by Engels at the beginning of their collaboration in the German-French Yearbooks, anticipated many of the ideas Marx later developed more thoroughly in Capital.

In a later scene—one of the most amusing in the film—Engels, Marx and Mary Burns encounter an employer friend of Engels senior in a London club. The entrepreneur, who employs children at his factory, stoutly maintains that night shifts do not affect their health. “You mean, they do not affect your health,” Mary Burns replies to the stunned employer.

Marx and Engels developed their historical materialist outlook on the eve of the bourgeois revolution, which swept across Europe in 1848, through fierce polemics with representatives of tendencies articulating the interests of bourgeois and middle-class layers, as well as conservative artisans.

The film gives much space to these disputes. In the course of the film we are introduced to, among many others, the young Hegelians Max Stirner and Bruno Bauer, the editor of the German-French Yearbooks Arnold Ruge, the French socialist Pierre Proudhon, the True Socialists Moses Hess and Karl Grün, and the utopian Wilhelm Weitling.

Although the dialogues are largely based on original sources, it is often difficult to understand what the disputes are about. One reason is the drama of the action. The film tries to portray the life of its protagonists—both are not yet 30—in all their aspects: love, birth, debauchery, material misery, conflicts with parents, etc. Peck said his intention was to put Marx, the “bearded old man,” aside and to revive “the exploits of this fabulous trio … in an explosive Europe under the thumb of censorship and on the eve of the bourgeois-democratic revolution.”

As a result, the political content of the disputes often remains obscure. Before the viewer has grappled with one topic, the film moves on to the next scene. Here, a somewhat slower pace would have been desirable. It’s worth watching the movie twice.

The last third of the film deals with the activities of Marx and Engels in the League of the Just. It shows that even at that time they worked intensively to establish an international party of the working class. Marx and Engels worked on basing the practice of the League on a properly thought out, scientific program. This required a rigorous struggle against various petty bourgeois tendencies, which exercised considerable influence on the League. The film reconstructs the political struggles that raged in the League with great intensity.

Marx and Engels experience a huge success when the League of the Just is transformed into the Communist League in 1847 and changes its central slogan from “All human beings are brothers” to “Proletarians of all countries, unite.” The second congress of the Communist League, attended by representatives from 30 branches from seven countries, including the US, then commissions Marx and Engels to write its program, the Communist Manifesto.

The film ends with Marx, Engels and Jenny working intensively on the Communist Manifesto, reading aloud paragraphs from this outstanding historic document.

If the film, despite its weaknesses, encourages young people to study Marxism, it will fulfill an important task.

(World Socialist Web Site, 15 March 2017)

A snatch of dialogue from the film, between Friedrich Engels (FE) and Jenny Marx (JM)

FE: You’re an extraordinary woman, Frau Marx.

JM: Jenny.

FE: You’re admirable. You could have had a rich and idle life with a fellow aristocrat, basking in luxury and envy.

JM: I escaped utter boredom, yes. Happiness requires rebellion. Rebellion against the establishment, the old world. That’s what I believe. And I hope to see the old world crack soon.

FE: The two of us. No. The three of us, Jenny. We’ll overthrow it…This old world.

JM: It might take more than three of us, don’t you think?

FE: There are probably some people here who weep when they hear the words kindness, gentleness and fraternity. But tears do not give power. Power does not shed tears. The bourgeoisie shows you no gentleness and you won’t conquer it with kindness.

Citizens, friends, comrades, Why are we here? Because we are fighting.

(Delegates: Yes, of course! Yes!)

FE: What are we fighting for?

(Delegates: Freedom! Equality! All men are brothers!)

FE: All men are brothers?

(Delegate: Yes!)

FE: You? And You?

(Delegates: Yes, of course.)

FE: Are the bourgeois and the workers brothers?

(Delegates: No!)

FE: No, they are not. They are enemies! We need to know what we have gathered here for. Is it for an abstract idea? A sentimental day-dream? How far will that get us? We need to know what the League wants, what it’s fighting for, for what society. And we have to decide that now.

The industrial revolution of today has created the modern slave. This slave is the proletariat. By freeing itself, it will free the whole of mankind. And that freedom has a name: Communism. That is why I propose to abolish that motto because it’s misleading and weak!

Here is our motto! Workers of all countries unite! I request that the League of the Just shall henceforth be called the Communist League!