The Russian Revolution – 7 November 1917. A 100 years after that momentous day, it is important to remind ourselves that that Revolution was no coup, no conspiracy. It was the greatest assertion the world has yet seen of democracy – of the urge and will of ordinary people for liberation.

In tribute to that moment in history, Liberation reproduces Lenin’s own article on the fourth anniversary of the revolution. We also carry some excerpts from October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, (Verso 2017) – a recent retelling of the story of the revolution by British writer China Miéville, and from some other sources, to highlight some of the remarkable and less recognized aspects of the revolution.

A few words of introduction are called for. Russia in 1917 followed the Julian calendar – which is 13 days behind the modern Gregorian calendar. This is why the ‘October Revolution’ of October 25 1917 is now called the November Revolution.

My Champion Is The People

On 17 March “Delo naroda, the SR newspaper, told its readers that they had been lied to, that not only were fairy stories real but that they were living through one. Once upon a time, it continued, ‘there lived a huge old dragon’, which devoured the best and bravest citizens ‘in the haze of madness and power’. But a valiant hero had appeared, a collective hero. ‘My champion’, wrote Delo naroda, ‘is the people.’ The hour has come for the beast’s end, The old dragon will coil up and die.”(October)

The story of the Russian Revolution is a lesson in the speed with which history can move and epochs can change. The period after 1907 was a period of setback and despondency for the revolutionary Left in Russia; its leaders forced into exile, its membership plummeting. And yet within a decade, things changed rapidly. In March 1917, a massive popular upsurge overthrew the Tsar and established a Provisional Government headed by the then immensely popular Kerensky. Edward Dune, a young teenager in Moscow, described how most of the people in the massive crowd of demonstrators “that morning had been praying for the good health of the imperial family. Now they were shouting, “Down with the tsar!” and not disguising their joyful contempt.” (Miéville, October)

The new Government enjoyed plenty of popular support to begin with. But the March 1917 moment had also given birth to another centre of democratic power: “From the streets, meanwhile, as this continued, had arisen another kind of control. Some of the insurgents recalled those councils of 1905, those soviets. Activists and streetcorner agitators had already begun to call for their return, in leaflets, in boisterous voices from the crowds.”

The new Government enjoyed plenty of popular support to begin with. But the March 1917 moment had also given birth to another centre of democratic power: “From the streets, meanwhile, as this continued, had arisen another kind of control. Some of the insurgents recalled those councils of 1905, those soviets. Activists and streetcorner agitators had already begun to call for their return, in leaflets, in boisterous voices from the crowds.”

(October) And soon after, the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies was born. The Soviet reflected a broad spectrum of the 1917 Russian Left. Between March and November, again, history moved fast. As disillusionment with and anger against the Provisional Government grew among people, the demand grew that the Soviet directly take power. But within the Soviet, amongst the Russian Left, opinion was divided about taking power. The Soviet leadership hesitated to take power, holding on to the notion that the democratic revolution needed an alliance with the bourgeoisie and bourgeois leadership, rather than exclusively proletarian leadership which must wait for a future stage of socialist revolution. Meanwhile, in the interim, the Bolsheviks and Lenin in particular were branded as traitors to Russia, and there was a (partially successful) attempt to whip up some national chauvinist sentiments against them. But as the popular mood in favour of ‘Bread, Peace, and Land’ grew, the Bolshevik Party’s consistency on these questions paid off, and support for it grew exponentially, culminating in the proletarian revolution of November 1917.

The point to be underlined here is the relationship between the people and the revolutionary party. The proletarian revolution did not take place out of some subjective wish of the Bolshevik leadership – it was not a coup planned and achieved by Lenin and his party. The people’s determination to win Bread, Peace, and Land – to liberate themselves not only from the yoke of the Tsar but from oppression in factories and fields, to end a hated war, to achieve human dignity as workers, as women, as oppressed nationalities and rank-and-file soldiers – found expression first in the March revolution. But when the Provisional Government thanks to its very nature betrayed those goals, the people began to wish to take power directly into their own hands – and saw in the Bolshevik party the means, the organized force, and the vision to do so.

Workers Assert Democracy and Dignity

What did the revolution mean to Russia’s workers?

In the months between March and November 1917, workers had already begun to experience and assert direct democracy in the Soviets – taking decisions without waiting for the Provisional Government’s opinion or approval. Miéville describes it this way: “… in Petrograd, the Soviet agreed with the factory owners that long-demanded eight-hour day, as well as the principle of worker-elected factory committees and a system of industrial arbitration…. Unpopular foremen were shoved in wheelbarrows and tipped into nearby canals. When the Moscow bosses resisted the eight-hour day, on 18 March the Moscow Soviet, recognising what workers were instituting as a fait accompli, simply decreed it, bypassing the Provisional Government. And their decree stood.”

And the workers’ concerns were not just for wages and working hours – they asserted, above all, a newfound sense of human dignity. In the wake of the March revolution, “Demonstrations voiced existential demands, even at the expense of income. ‘No tips taken here’, said the signs on restaurant walls. Petrograd waiters struck for dignity. They marched in their best clothes under banners denouncing the ‘indignity’ of tipping, the stench of noblesse oblige. They demanded ‘respect for waiters as human beings’.” (Miéville, October)

“Take Power When It’s Given To You!”

Onwards from 16 July 1917, postal workers, and soldiers being recalled to the war were gathering on the streets of Petrograd as a “seething, angry mass.” Even as the demonstrations surged on to the streets, attempts by Soviet leaders to calm them down failed. The massive demonstration converged on the headquarters of the Soviet on 17 July, shouting their demand: “all power to the soviets.” The Soviet leadership (hesitant to take power and instead determined to keep supporting the Provisional Government) sent out one of their most popular and well-liked leaders, Chernov, to speak to the demonstrators and calm them down. “A big worker pushed his way through and came up close and shook his fist in Chernov’s face. ‘Take power, you son of a bitch,’ he bellowed, in one of most famous phrases of 1917, ‘when it’s given to you!’” (Miéville, October)

Onwards from 16 July 1917, postal workers, and soldiers being recalled to the war were gathering on the streets of Petrograd as a “seething, angry mass.” Even as the demonstrations surged on to the streets, attempts by Soviet leaders to calm them down failed. The massive demonstration converged on the headquarters of the Soviet on 17 July, shouting their demand: “all power to the soviets.” The Soviet leadership (hesitant to take power and instead determined to keep supporting the Provisional Government) sent out one of their most popular and well-liked leaders, Chernov, to speak to the demonstrators and calm them down. “A big worker pushed his way through and came up close and shook his fist in Chernov’s face. ‘Take power, you son of a bitch,’ he bellowed, in one of most famous phrases of 1917, ‘when it’s given to you!’” (Miéville, October)

Peasants’ Movements

The March revolution ripened into November – and the growing assertion of the peasantry was one of the foremost signs of this maturing revolution. In the Volga region, “rural communes began disputing with landowners over rent and rights to the commons. Gangs of peasants were increasingly wont to make their way into private woods with axes and saws and fell the estate’s trees.” In the north-west districts, “peasants simply began to mow the gentry’s meadows for their own use, paying only the prices they reckoned were fair for seed. That sense of ‘fairness’ was crucial. Certainly there were moments of crude class rage and cruelty. But the actions of village communes against landlords were often scrupulously articulated in terms of a moral economy of justice.”

From all over Russia, illiterate peasants got scribes to write letters to the Soviet, to the Government, to the various Left parties, experiencing the thrill of self-expression. They wrote demanding that feudal lands, lands belonging to monasteries, churches and estate owners “must be surrendered to the people without compensation.” Some wrote demanding socialist newspapers, others lamented their lack of education and asked for books; others sent meager amounts of money for the revolution. The Rakalovsk peasants sent a letter saying, “We are sick and tired of living in debt and slavery – we want space and light.”

Support for the Bolsheviks grew among the poor peasants. The First All-Russian Congress of Peasants’ Soviets took place in Petrograd in May. “Reflecting the overlap between peasantry and soldiery, close to half the 1,200 accredited delegates” were soldiers from the front. “Despite the Bolsheviks’ tiny presence – a minuscule group of nine, accompanied by a caucus of fourteen ‘non-party’ delegates who tended to vote with them – their influence was growing. This was, in particular, because of their harder, more coherent and clearly expressed positions on the two key questions of war and land, as laid out in an open letter from Lenin to the Congress…he addressed the delegates in person, hammering home his support for the poorest peasants and demanding the redistribution of land.”

Soldiers Sick And Tired Of War, Impatient For Peace

In 2014, Vladimir Putin addressed a youth camp, telling them, “Regardless of how hurtful it might be to hear this, perhaps even to some of this audience, people who hold leftist views, but in the first world war, the Bolsheviks wished to see their fatherland defeated. While heroic Russian soldiers and officers shed their blood at the front, some were shaking Russia from within. They shook it to the point that Russia as a state collapsed and declared itself defeated by a country that had lost the war. …This was a complete betrayal of the national interest!”

In 2014, Vladimir Putin addressed a youth camp, telling them, “Regardless of how hurtful it might be to hear this, perhaps even to some of this audience, people who hold leftist views, but in the first world war, the Bolsheviks wished to see their fatherland defeated. While heroic Russian soldiers and officers shed their blood at the front, some were shaking Russia from within. They shook it to the point that Russia as a state collapsed and declared itself defeated by a country that had lost the war. …This was a complete betrayal of the national interest!”

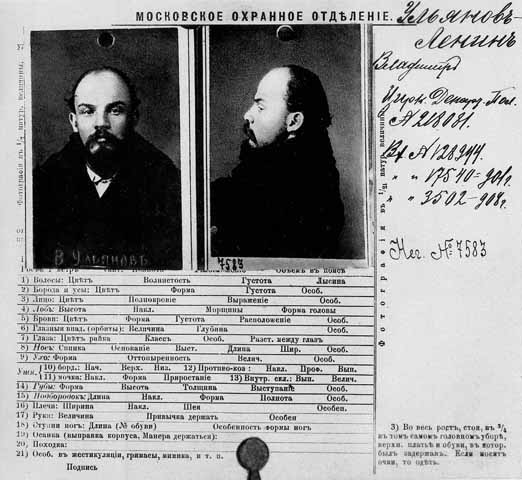

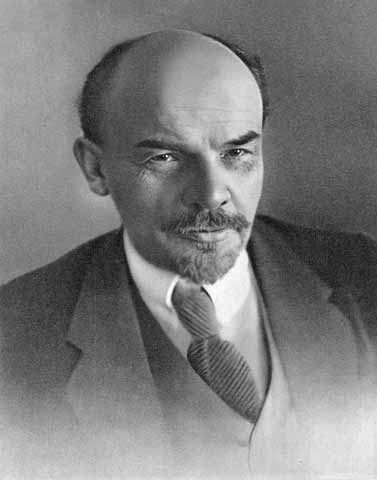

Putin is attempting to rewrite history. He knows that Lenin is still viewed as a positive figure by a majority of Russians – and he is trying to change that perception. (A poll conducted by the Levada Center in May 2013 found that 40 percent of Russians had a “somewhat positive” view of Lenin; 15 percent had a “positive” view of Lenin; 18 percent had a “somewhat negative” view of him; 16 percent were undecided and 1 percent did not know who he was.)

From the poem “Russian Revolution” ( Mikhail Kuzmin, 1917)

Putin’s version of history tries to erase the fact that way back in 1917 too, there were many attempts to portray the Bolsheviks as traitors to the fatherland – and these proved to be in vain, because the growing disgust for World War I among the poor peasants, soldiers, and women overwhelmed any chauvinist sentiments.

In 1915, at the Zimmerwald conference of the Second International, the right flank of the Mensheviks and SRs had claimed that Russia’s revolution would be “pro-war rather than pacifist”. This “social patriotism” – patriotism of the social democrats – effectively rendered the International defunct. For Lenin and the Bolsheviks, revolutionary internationalism went together with a commitment to peace and a firm opposition to war.

Meanwhile, all across Europe, the terrible nature of modern warfare, experienced for the first time in World War I, was giving birth to anti-war sentiment even amongst soldiers in the trenches. The English poet Wilfred Owen wrote in 1918, that his poetry was not “about glory, honour, might, majesty, dominion, or power” – “Above all I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War.” An entire generation of English “war poets”, writing straight from the trenches, described the sheer horror and inhumanity of war; defying jingoistic war-mongering by civilians, these soldier-poets insisted on recognising “enemy” soldiers as humans, even as friends.

In Russia, widespread anti-war sentiment among the peasantry and soldiers was a huge factor spurring the March and November revolutions. October quotes a grassroots soldiers’ song expressing deep-seated resentment among the military rank-and-file against the high-handedness of officers:

Sure we’d like some tea

But give us with our tea

Some polite respect

And please have officers

Not slap us in the face.

During the March revolution, workers’ demonstrations met with displays of solidarity from contingents of soldiers. On one occasion, 2500 Vyborg mill-workers found themselves face to face with a dreaded Cossack contingent of horseback soldiers. Officers ordered the Cossacks to block the street – and the soldiers obeyed: “With their legendary equestrian skills, they lined up their horses into a living blockade breathing out mist. Again, in their very obedience was dissent. Ordered to be still, still they remained. They did not move as the boldest marchers crept closer. The Cossacks did not move as the strikers approached, their eyes widening as at last they understood the unspoken invitation in the preternatural immobility of mounts and men, as they ducked below the bellies of the motionless horses to continue their march. Rarely have skills imparted by reaction been so exquisitely deployed against it.” (October)

One of the most important documents of the March revolution was “Order Number 1” – a seven-point order drafted by the soldiers themselves: that decreed “1) election of soldiers’ committees in military units; 2)election of their representatives to the Soviet; 3)subordination of soldiers to the Soviet in political actions; 4)subordination of soldiers to the Military Commission – in so far, again and crucially, as its orders did not deviate from the Soviet’s; 5)control of weapons by soldiers’ committees; 6)military discipline while on duty, with full civil rights at other times; 7) abolition of officers’ honorary titles and of officers’ use of derogatory terms for their men.” The poet Mikhail Kuzmin wrote that soldiers, like workers, “demanded to be addressed with the respectful ‘Citizen’, a term spreading so widely it was as if it had been ‘invented just now!’” (October)

A young Ukranian deserter Aleksandr Dneprovskiy, his his diary A Deserter’s Notes, bitterly described the patriotic press as “tubs of printed slop … poured over the heads of long-suffering humanity.” By June and July, mass desertions from the front were the order of the day: “By the hot days of July, more than 50,000 deserters were in the city….As the war grew ever more hated, people remembered the Bolshevik party’s unwavering opposition to it.” (October)

In spite of this widespread opposition to the war, attempts to brand the Bolsheviks as “traitors” continued to have some traction. In July 1917, right wing papers published “fake news” claiming that Lenin was a German spy. For a while, this provoked suspicion and even violence against the Bolsheviks among the people. Not only did the right wing feel emboldened to attack Bolsheviks – “A Pravda distributor was killed on the street” – the rumours had an impact even on the Left, among workers. “One party activist, E. Tarasova, came into a Vyborg factory she knew well, and instantly the women workers she had been speaking to days earlier screamed abuse, calling her a German spy, and hurled nuts and bolts at her, savagely cutting her hands and face. A Menshevik, they explained, shamefaced, when the panic abated, had been agitating against the Bolsheviks.”

…This is the last of you, old world – Soon we’ll smash you to bits.

From The Twelve, Alexander Blok, translated by Robert Chandler

But the anti-war sentiment was so strong that such prejudice and frenzy against the Bolsheviks dissipated quickly. In August, a soldier, Kuchlavok, and his regiment sent a letter to the Soviet paper Izvestia asking “They used to say that the war was foisted off on us by Nicholas. Nicholas has been overthrown, so who is foisting the war on us now?” Another group of soldiers sent the Soviet Executive Committee a letter asking, “All of us … ask you as our comrades to explain to us who these Bolsheviks are … Our provisional government has come out very much against the Bolsheviks. But we … don’t find any fault with them.’”

Women Dreaming of Equality, Bread, and Peace

The March revolution began on International Women’s Day – 8 March 1917. The Left parties had organized meetings in factories to commemorate the day – but they did not plan what happened next:

“women began to pour from the factories onto the streets, shouting for bread. They marched through the city’s most militant districts – Vyborg, Liteiny, Rozhdestvenskii – hollering to people gathered in the courtyards of the blocks, filling the wide streets in huge and growing numbers, rushing to the factories and calling on the men to join them….Abruptly, without anyone having planned it, almost 90,000 women and men were roaring on the streets of Petrograd. And now they were not shouting only for bread, but for an end to the war. An end to the reviled monarchy….They gathered in great crowds by barracks and army hospitals. There they struck up conversations with curious and friendly soldiers.” (October)

“women began to pour from the factories onto the streets, shouting for bread. They marched through the city’s most militant districts – Vyborg, Liteiny, Rozhdestvenskii – hollering to people gathered in the courtyards of the blocks, filling the wide streets in huge and growing numbers, rushing to the factories and calling on the men to join them….Abruptly, without anyone having planned it, almost 90,000 women and men were roaring on the streets of Petrograd. And now they were not shouting only for bread, but for an end to the war. An end to the reviled monarchy….They gathered in great crowds by barracks and army hospitals. There they struck up conversations with curious and friendly soldiers.” (October)

The old sexist taunts and jeers lost their ability to intimidate and shame women: “The heaving streets rang with revolutionary songs. Seeing workers from the Promet factory marching behind a woman, a Cossack officer jeered that they were following a baba, a hag. Arishina Kruglova, the Bolshevik in question, yelled back that she was an independent woman worker, a wife and sister of soldiers at the front. At her riposte, the troops who faced her lowered their guns.” (October)

During the March revolution, women also demanded the right to vote. The provisional government was hesitant to grant this demand. “Many even in the revolutionary movement were hesitant, warning that, though they supported the equality of women ‘in principle’, concretely Russia’s women were politically ‘backward’, and their votes therefore risked hindering progress. On her return to the country on the 18th, Kollontai took those prejudices head-on. ‘But wasn’t it we women, with our grumbling about hunger, about the disorganisation in Russian life, about our poverty and the sufferings born of the war, who awakened a popular wrath?’ she demanded. The revolution, she pointed out, was born on International Women’s Day, ‘And didn’t we women go first out to the streets in order to struggle with our brothers for freedom, and even if necessary to die for it?” (October)

During the March revolution, women also demanded the right to vote. The provisional government was hesitant to grant this demand. “Many even in the revolutionary movement were hesitant, warning that, though they supported the equality of women ‘in principle’, concretely Russia’s women were politically ‘backward’, and their votes therefore risked hindering progress. On her return to the country on the 18th, Kollontai took those prejudices head-on. ‘But wasn’t it we women, with our grumbling about hunger, about the disorganisation in Russian life, about our poverty and the sufferings born of the war, who awakened a popular wrath?’ she demanded. The revolution, she pointed out, was born on International Women’s Day, ‘And didn’t we women go first out to the streets in order to struggle with our brothers for freedom, and even if necessary to die for it?” (October)

On 1st April 1917, a massive procession of 40000 demonstrators (mostly women, but also many men) marched to demand women’s right to vote. Note, they marched to the Soviet headquarters, not the Provincial Government! Their banners read: “If the woman is a slave, there will be no freedom.” The demonstration forced the Soviet and Provincial Government leaders to draft a bill for universal adult suffrage, which was passed in July. Because the demonstration for the right to vote was a cross-class, broad spectrum one, it also included those who were pro-war.

But anti-war sentiment among women grew stronger and stronger. “In early April, thousands of soldiers’ wives – soldatki – marched through the capital. These women had started the war disadvantaged, browbeaten and precarious, desperate for charity and inadequate state support. But the absence of their husbands could also mean an unexpected liberation. In February their demands for food, support, respect, had started to take on a radical bent. That trend continued. In Kherson province, one observer saw the soldatki forcing their way into homes and ‘requisitioning’ any luxury they thought was undeserved. Not only did they flout laws and intimidate the authorities wherever they possibly could, there were also direct acts of violence. The state flour trader who did not want to offer them his goods at discounted price was beaten by a band of soldiers’ wives, and the pristav, the local police chief, who wanted to hurry to his help, escaped the same fate by a hair’s breadth.” (October)

In May, “Nina Gerd, the organiser of the Committee for the Relief of Soldiers’ Wives in the Vyborg district, a liberal but an old friend of Krupskaya, surrendered to her the organisation. Three years before, in the recollection of one philanthropist, the soldatki had been ‘helpless creatures’, ‘blind moles’, pleading with the authorities for help. Now, as she relinquished the committee, Gerd told Krupskaya that the women ‘do not trust us; they are displeased with whatever we do; they have faith only in the Bolsheviks’. Soon the soldatki were self-organising in their own soviets.””

National and Religious Minorities Seek Self-Determination

In the revolutionary climate that followed March and built up to November, national minorities (that in many cases also represented religious minorities) rose up against Russian chauvinism and began to pursue self-determination.

“The predominantly Buddhist Buryat region of Siberia had …more than once in subsequent years … been rocked by Buryat revolts against discriminatory laws, and it had faced chauvinist cultural and political threats from the Russian regime. In 1905 a Buryat congress had called for rights to self-government and linguistic–cultural freedom: it had been suppressed. Now, with the new wave of freedoms, came a new Congress in Irkutsk – which voted in favour of independence….

“Buoyed by the February revolution, and feeling it vindicated their own programme, members of the progressive, modernizing Muslim Jadidist movement set up an Islamic Council in Tashkent, Turkestan, and across the region, helping to dismantle the old government structures – already undermined by the spread of local soviets – and enhancing the role of the indigenous Muslim population. At the end of the month, the council convened the first Pan-Turkestan Muslim Congress in the city. Its 150 delegates recognised the Provisional Government, and unanimously called for substantial regional autonomy.” (October)

Along with the assertion of self-determination, there were also democratic stirrings within communities and oppressed nationalities. At the All-Russian Muslim Women’s Congress held in May in Kazan in Tatarstan, “fifty-nine women delegates met before an audience 300 strong, overwhelmingly female, to debate issues including the status of Sharia law, plural marriage, women’s rights and the hijab. Contributions came from a range of political and religious positions, from socialists like Zulaykha Rahmanqulova and the twenty-two-year-old poet Zahida Burnasheva, as well as from the religious scholars Fatima Latifiya and Labiba Huseynova, an expert on Islamic law….Delegates debated whether Quranic injunctions were historically specific. Even many proponents of trans-historical orthodoxy interpreted the texts to insist, against conservative voices, that women had the right to attend mosque, or that polygyny was only permitted – a crucial caveat – if it was ‘just’; that is, with the permission of the first wife. Unsatisfied when the gathering approved that progressive-traditionalist position on plural marriage, the feminists and socialists mandated three of their number, including Burnasheva, to attend the All-Russian Muslim Conference in Moscow the next month, to put their alternative case against polygyny. The conference passed ten principles, including women’s right to vote, the equality of the sexes, and the non-compulsory nature of the hijab.”

The All-Russian Muslim Conference in Moscow was attended by 900 delegates from Muslim populations and nations – Bashkirs, Ossets, Turks, Tatars, Kirghiz and more. “Almost a quarter of those present were women, several fresh from the Women’s Muslim Congress in Kazan; one of the twelve-person presidium committee was a Tatar woman, Selima Jakubova. When one man asked why men should grant women political rights, a woman jumped up to answer. ‘You listen to the men of religion and raise no objections, but act as though you can grant us rights,’ she said. ‘Rather than that, we shall seize them!’” Finally, at the conference, “a powerful programme of women’s rights was adopted, and, as the left at the Women’s Congress had advocated, polygyny was banned, if only symbolically. Against the plans of the powerful Tatar bourgeoisie for extraterritorial cultural–national autonomy, and against pan-Islamic aspirations, the conference advocated a federalist position of cultural autonomy. This could, and indeed would, mature into calls for national liberation.”

Revolutionising All Aspects of Life

There was scarcely any aspect of life that was not utterly transformed by the Russian revolution. Lenin’s piece reproduced by us touches upon the most significant changes in the lives of workers, peasants, oppressed nationalities and women: that made it a much deeper and more consistent democracy that any bourgeois democracy.

There was scarcely any aspect of life that was not utterly transformed by the Russian revolution. Lenin’s piece reproduced by us touches upon the most significant changes in the lives of workers, peasants, oppressed nationalities and women: that made it a much deeper and more consistent democracy that any bourgeois democracy.

A few other remarkable advances deserve our attention. The revolution made a bold bid to transform the patriarchal family; in Lenin’s words, “We really razed to the ground the infamous laws placing women in a position of inequality, restricting divorce and surrounding it with disgusting formalities, denying recognition to children born out of wedlock, enforcing a search for their fathers, etc., laws numerous survivals of which, to the shame of the bourgeoisie and of capitalism, are to be found in all civilised countries.” (A Great Beginning, June 1919) On women’s demand, abortion too was legalized, giving women a measure of control over the size of their families. In that piece Lenin candidly acknowledged that “Notwithstanding all the laws emancipating woman, she continues to be a domestic slave, because petty housework crushes, strangles, stultifies and degrades her, chains her to the kitchen and the nursery, and she wastes her labour on barbarously unproductive, petty, nerve-racking, stultifying and crushing drudgery. The real emancipation of women, real communism, will begin only where and when an all-out struggle begins (led by the proletariat wielding the state power) against this petty housekeeping.” Lenin stressed that the solution lay in nurturing the “shoots” which already existed in capitalism: “Public catering establishments, nurseries, kindergartens — here we have examples of these shoots, here we have the simple, everyday means, involving nothing pompous, grandiloquent or ceremonial, which can really emancipate women, really lessen and abolish their inequality with men as regards their role in social production and public life…. Public catering establishments, nurseries, kindergartens — here we have examples of these shoots, here we have the simple, everyday means, involving nothing pompous, grandiloquent or ceremonial, which can really emancipate women, really lessen and abolish their inequality with men as regards their role in social production and public life.” Spurred by Lenin, the fledgling Soviet state did in fact make an enormous advance in this field, thus bringing women in very large numbers into the workforce and into public life.

Another remarkable blow to patriarchy was struck by the Bolshevik Revolution when it struck down the tsarist-era laws criminalizing homosexuality. A 1923 pamphlet The Sexual Revolution in Russia, written by Dr. Grigorii Batkis, director of the Moscow Institute of Social Hygiene declared: “The present sexual legislation in the Soviet Union is the work of the October Revolution. This revolution is important not only as a political phenomenon, which secures the political rule of the working class. But also for the revolutions which emanating from it reach out into all areas of life…Soviet legislation bases itself on the following principle: It declares the absolute noninterference of the state and society into sexual matters, so long as nobody is injured, and no one’s interests are encroached upon. [Emphasis in original.]

Another remarkable blow to patriarchy was struck by the Bolshevik Revolution when it struck down the tsarist-era laws criminalizing homosexuality. A 1923 pamphlet The Sexual Revolution in Russia, written by Dr. Grigorii Batkis, director of the Moscow Institute of Social Hygiene declared: “The present sexual legislation in the Soviet Union is the work of the October Revolution. This revolution is important not only as a political phenomenon, which secures the political rule of the working class. But also for the revolutions which emanating from it reach out into all areas of life…Soviet legislation bases itself on the following principle: It declares the absolute noninterference of the state and society into sexual matters, so long as nobody is injured, and no one’s interests are encroached upon. [Emphasis in original.]

Concerning homosexuality, sodomy, and various other forms of sexual gratification, which are set down in European legislation as offenses against public morality—Soviet legislation treats these exactly the same as so-called “natural” intercourse. All forms of sexual intercourse are private matters. Only when there’s use of force or duress, as in general when there’s an injury or encroachment upon the rights of another person, is there a question of criminal prosecution.” (Sexuality and Socialism: History, Politics, and Theory of LGBT Liberation, Sherry Wolf, Haymarket Books, 2009)

As a result of this principled and progressive policy, revolutionary Russia even saw homosexual marriages being approved by Courts, sex-change operations being conducted in the 1920s, and transgender and gay people being able to live freely and with dignity. Many public figures of Soviet Russia of this period were openly gay: such as the commissar of public affairs Grigorii Chicherin who was a prominent face of the revolution abroad, or the prominent poet Mikhail Kuzmin, author of the first known gay-positive novel in any language, Wings.

Resonances in India

The November revolution transformed Russia – and in doing so, fired the imagination of people all over the world. In India, too, its impact was felt among the freedom fighters. Ten days after the revolution in Russia, a Calcutta nationalist daily Dainik Basumati wrote: “The downfall of Tsardom has ushered in the age of destruction of alien bureaucracy in India too”. A whole range of revolutionary organizations and individuals were inspired by the November revolution: including groups like Anushilan Samity and Yugantar; the Ghadar movement; leaders like SA Dange of Bombay and M Singaravelu of Madras.

Bhagat Singh and his comrades too were drawn to Leninist ideas of revolution and party building. Ashfaqullah – martyred in the Kakori Conspiracy Case – had been elected by Bhagat Singh and other comrades to travel to Russia, but could never make that journey.

On January 21, 1930, on the occasion of Lenin’s death anniversary, during their trial in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, Bhagat Singh and his comrades appeared in the court wearing red scarves, and raised slogans of “Long Live Socialist Revolution”, “Long Live Communist International”, “Long Live People” “Lenin’s Name Will Never Die”, and “Down with Imperialism”. Then, Bhagat Singh read aloud in open court the text of a telegram to be sent to the Third International: “On Lenin day we send hearty greetings to all who are doing something for carrying forward the ideas of the great Lenin. We wish success to the great experiment Russia is carrying out. We join our voice to that of the international working class movement. The proletariat will win. Capitalism will be defeated. Death to Imperialism.”

Not only those on the Left: other prominent Indians too were affected by the November Revolution. Rabindranath Tagore, who visited Russia in 1930, wrote in Russiar Chithi (Letters from Russia), commenting especially on its internationalism, “Their message of the Revolution is true for all the world. Here is a people on earth today who put the interest of all mankind above their own.”

The November Revolution is best remembered by the possibilities, promises, the striving and the hope of the moment of its birth and its early years. In the difficult years that followed, many mistakes were made, and the initial promise foundered and was eventually reversed. Revolutionaries all over the world will no doubt learn from its mistakes and missteps – but above all will be inspired by the bold confidence with which ordinary workers and peasants sought to reshape the world and make the brave bid towards human liberation.

Fourth Anniversary of the October Revolution

V.I. Lenin

(First published Pravda No. 234, October 18, 1921)

The fourth anniversary of October 25 (November 7) is approaching.

The farther that great day recedes from us, the more clearly we see the significance of the proletarian revolution in Russia, and the more deeply we reflect upon the practical experience of our work as a whole.

The farther that great day recedes from us, the more clearly we see the significance of the proletarian revolution in Russia, and the more deeply we reflect upon the practical experience of our work as a whole.

Very briefly and, of course, in very incomplete and rough outline, this significance and experience may be summed up as follows.

The direct and immediate object of the revolution in Russia was a bourgeois-democratic one, namely, to destroy the survivals of medievalism and sweep them away completely, to purge Russia of this barbarism, of this shame, and to remove this immense obstacle to all culture and progress in our country.

And we can justifiably pride ourselves on having carried out that purge with greater determination and much more rapidly, boldly and successfully, and, from the point of view of its effect on the masses, much more widely and deeply, than the great French Revolution over one hundred and twenty-five years ago.

Both the anarchists and the petty-bourgeois democrats (i.e., the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries, who are the Russian counterparts of that international social type) have talked and are still talking an incredible lot of nonsense about the relation between the bourgeois-democratic revolution and the socialist (that is, proletarian) revolution. The last four years have proved to the hilt that our interpretation of Marxism on this point, and our estimate of the experience of former revolutions were correct. We have consummated the bourgeois-democratic revolution as nobody had done before. We are advancing towards the socialist revolution consciously, firmly and unswervingly, knowing that it is not separated from the bourgeois-democratic revolution by a Chinese Wall, and knowing too that (in the last analysis) struggle alone will determine how far we shall advance, what part of this immense and lofty task we shall accomplish, and to what extent we shall succeed in consolidating our victories. Time will show. But we see even now that a tremendous amount—tremendous for this ruined, exhausted and backward country—has already been done towards the socialist transformation of society.

Let us, however, finish what we have to say about the bourgeois-democratic content of our revolution. Marxists must understand what that means. To explain, let us take a few striking examples.

The bourgeois-democratic content of the revolution means that the social relations (system, institutions) of the country are purged of medievalism, serfdom, feudalism.

What were the chief manifestations, survivals, remnants of serfdom in Russia up to 1917? The monarchy, the system of social estates, landed proprietorship and land tenure, the status of women, religion, and national oppression. Take any one of these Augean stables, which, incidentally, were left largely uncleansed by all the more advanced states when they accomplished their bourgeois-democratic revolutions one hundred and twenty-five, two hundred and fifty and more years ago (1649 in England); take any of these Augean stables, and you will see that we have cleansed them thoroughly. In a matter of ten weeks, from October 25 (November 7), 1917 to January 5, 1918, when the Constituent Assembly was dissolved, we accomplished a thousand times more in this respect than was accomplished by the bourgeois democrats and liberals (the Cadets) and by the petty-bourgeois democrats (the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries) during the eight months they were in power.

Those poltroons, gas-bags, vainglorious Narcissuses and petty Hamlets brandished their wooden swords—but did not even destroy the monarchy! We cleansed out all that monarchist muck as nobody had ever done before. We left not a stone, not a brick of that ancient edifice, the social-estate system even the most advanced countries, such as Britain, France and Germany, have not completely eliminated the survivals of that system to this day!), standing. We tore out the deep-seated roots of the social-estate system, namely, the remnants of feudalism and serfdom in the system of landownership, to the last. “One may argue” (there are plenty of quill-drivers, Cadets, Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries abroad to indulge in such arguments) as to what “in the long run” will be the outcome of the agrarian reform effected by the Great October Revolution. We have no desire at the moment to waste time on such controversies, for we are deciding this, as well as the mass of accompanying controversies, by struggle. But the fact cannot be denied that the petty-bourgeois democrats “compromised” with the landowners, the custodians of the traditions of serfdom, for eight months, while we completely swept the landowners and all their traditions from Russian soil in a few weeks.

Take religion, or the denial of rights to women, or the oppression and inequality of the non-Russian nationalities. These are all problems of the bourgeois-democratic revolution. The vulgar petty-bourgeois democrats talked about them for eight months. In not a single one of the most advanced countries in the world have these questions been completely settled on bourgeois-democratic lines. In our country they have been settled completely by the legislation of the October Revolution. We have fought and are fighting religion in earnest. We have granted all the non-Russian nationalities their own republics or autonomous regions. We in Russia no longer have the base, mean and infamous denial of rights to women or inequality of the sexes, that disgusting survival of feudalism and medievalism, which is being renovated by the avaricious bourgeoisie and the dull-witted and frightened petty bourgeoisie in every other country in the world without exception.

Take religion, or the denial of rights to women, or the oppression and inequality of the non-Russian nationalities. These are all problems of the bourgeois-democratic revolution. The vulgar petty-bourgeois democrats talked about them for eight months. In not a single one of the most advanced countries in the world have these questions been completely settled on bourgeois-democratic lines. In our country they have been settled completely by the legislation of the October Revolution. We have fought and are fighting religion in earnest. We have granted all the non-Russian nationalities their own republics or autonomous regions. We in Russia no longer have the base, mean and infamous denial of rights to women or inequality of the sexes, that disgusting survival of feudalism and medievalism, which is being renovated by the avaricious bourgeoisie and the dull-witted and frightened petty bourgeoisie in every other country in the world without exception.

All this goes to make up the content of the bourgeois-democratic revolution. A hundred and fifty and two hundred and fifty years ago the progressive leaders of that revolution (or of those revolutions, if we consider each national variety of the one general type) promised to rid mankind of medieval privileges, of sex inequality, of state privileges for one religion or another (or “religious ideas ”, “the church” in general), and of national inequality. They promised, but did not keep their promises. They could not keep them, for they were hindered by their “respect”— for the “sacred right of private property”. Our proletarian revolution was not afflicted with this accursed “respect” for this thrice-accursed medievalism and for the “sacred right of private property”.

But in order to consolidate the achievements of the bourgeois-democratic revolution for the peoples of Russia, we were obliged to go farther; and we did go farther. We solved the problems of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in passing, as a “by-product” of our main and genuinely proletarian -revolutionary, socialist activities. We have always said that reforms are a by-product of the revolutionary class struggle. We said—and proved it by deeds—that bourgeois-democratic reforms are a by-product of the proletarian, i.e., of the socialist revolution. Incidentally, the Kautskys, Hilferdings, Martovs, Chernovs, Hillquits, Longuets, MacDonalds, Turatis and other heroes of “Two and-a-Half” Marxism were incapable of understanding this relation between the bourgeois-democratic and the proletarian-socialist revolutions. The first develops into the second. The second, in passing, solves the problems of the first. The second consolidates the work of the first. Struggle, and struggle alone, decides how far the second succeeds in outgrowing the first.

The Soviet system is one of the most vivid proofs, or manifestations, of how the one revolution develops into the other. The Soviet system provides the maximum of democracy for the workers and peasants; at the same time, it marks a break with bourgeois democracy and the rise of a new, epoch-making type of democracy, namely, proletarian democracy, or the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Let the curs and swine of the moribund bourgeoisie and of the petty-bourgeois democrats who trail behind them heap imprecations, abuse and derision upon our heads for our reverses and mistakes in the work of building up our Soviet system. We do not forget for a moment that we have committed and are committing numerous mistakes and are suffering numerous reverses. How can reverses and mistakes be avoided in a matter so new in the history of the world as the building of an unprecedented type of state edifice! We shall work steadfastly to set our reverses and mistakes right and to improve our practical application of Soviet principles, which is still very, very far from being perfect. But we have a right to be and are proud that to us has fallen the good fortune to begin the building of a Soviet state, and thereby to usher in a new era in world history, the era of the rule of a new class, a class which is oppressed in every capitalist country, but which everywhere is marching forward towards a new life, towards victory over the bourgeoisie, towards the dictatorship of the proletariat, towards the emancipation of mankind from the yoke of capital and from imperialist wars.

The question of imperialist wars, of the international policy of finance capital which now dominates the whole world, a policy that must inevitably engender new imperialist wars, that must inevitably cause an extreme intensification of national oppression, pillage, brigandry and the strangulation of weak, backward and small nationalities by a handful of “advanced” powers—that question has been the keystone of all policy in all the countries of the globe since 1914. It is a question of life and death for millions upon millions of people. It is a question of whether 20,000,000 people (as compared with the 10,000,000 who were killed in the war of 1914-18 and in the supplementary “minor” wars that are still going on) are to be slaughtered in the next imperialist war, which the bourgeoisie are preparing, and which is growing out of capitalism before our very eyes. It is a question of whether in that future war, which is inevitable (if capitalism continues to exist), 60,000,000 people are to be maimed (compared with the 30,000,000 maimed in 1914-18). In this question, too, our October Revolution marked the beginning of a new era in world history. The lackeys of the bourgeoisie and its yes-men—the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks, and the petty-bourgeois, allegedly “socialist”, democrats all over the world—derided our slogan “convert the imperialist war into a civil war”. But that slogan proved to be the truth—it was the only truth, unpleasant, blunt, naked and brutal, but nevertheless the truth, as against the host of most refined jingoist and pacifist lies. Those lies are being dispelled. The Brest peace has been exposed. And with every passing day the significance and consequences of a peace that is even worse than the Brest peace—the peace of Versailles—are being more relentlessly exposed. And the millions who are thinking about the causes of the recent war and of the approaching future war are more and more clearly realising the grim and inexorable truth that it is impossible to escape imperialist war, and imperialist peace (if the old orthography were still in use, I would have written the word mir in two ways, to give it both its meanings) [In Russian, the word mir has two meanings (world and peace) and had two different spellings in the old orthography.—Translator] which inevitably engenders imperialist war, that it is impossible to escape that inferno, except by a Bolshevik struggle and a Bolshevik revolution.

Let the bourgeoisie and the pacifists, the generals and the petty bourgeoisie, the capitalists and the philistines, the pious Christians and the knights of the Second and the Two-and-a-Half Internationals vent their fury against that revolution. No torrents of abuse, calumnies and lies can enable them to conceal the historic fact that for the first time in hundreds and thousands of years the slaves have replied to a war between slave-owners by openly proclaiming the slogan: “Convert this war between slave-owners for the division of their loot into a war of the slaves of all nations against the slave-owners of all nations.”

For the first time in hundreds and thousands of years that slogan has grown from a vague and helpless waiting into a clear and definite political programme, into an effective struggle waged by millions of oppressed people under the leadership of the proletariat; it has grown into the first victory of the proletariat, the first victory in the struggle to abolish war and to unite the workers of all countries against the united bourgeoisie of different nations, against the bourgeoisie that makes peace and war at the expense of the slaves of capital, the wage-workers, the peasants, the working people.

This first victory is not yet the final victory, and it was achieved by our October Revolution at the price of incredible difficulties and hardships, at the price of unprecedented suffering, accompanied by a series of serious reverses and mistakes on our part. How could a single backward people be expected to frustrate the imperialist wars of the most powerful and most developed countries of the world without sustaining reverses and without committing mistakes! We are not afraid to admit our mistakes and shall examine them dispassionately in order to learn how to correct them. But the fact remains that for the first time in hundreds and thousands of years the promise “to reply” to war between the slave-owners by a revolution of the slaves directed against all the slave-owners has been completely fulfilled—and is being fulfilled despite all difficulties.

We have made the start. When, at what date and time, and the proletarians of which nation will complete this process is not important. The important thing is that the ice has been broken; the road is open, the way has been shown.

Gentlemen, capitalists of all countries, keep up your hypocritical pretence of “defending the fatherland”—the Japanese fatherland against the American, the American against the Japanese, the French against the British, and so forth! Gentlemen, knights of the Second and Two-and a-Half Internationals, pacifist petty bourgeoisie and philistines of the entire world, go on “evading” the question of how to combat imperialist wars by issuing new “Basle Manifestos” (on the model of the Basle Manifesto of 1912[1]). The first Bolshevik revolution has wrested the first hundred million people of this earth from the clutches of imperialist war and the imperialist world. Subsequent revolutions will deliver the rest of mankind from such wars and from such a world.

Our last, but most important and most difficult task, the one we have done least about, is economic development, the laying of economic foundations for the new, socialist edifice on the site of the demolished feudal edifice and the semi-demolished capitalist edifice. It is in this most important and most difficult task that we have sustained the greatest number of reverses and have made most mistakes. How could anyone expect that a task so new to the world could be begun without reverses and without mistakes! But we have begun it. We shall continue it. At this very moment we are, by our New Economic Policy, correcting a number of our mistakes. We are learning how to continue erecting the socialist edifice in a small-peasant country without committing such mistakes.

The difficulties are immense. But we are accustomed to grappling with immense difficulties. Not for nothing do our enemies call us “stone-hard” and exponents of a “firm line policy”. But we have also learned, at least to some extent, another art that is essential in revolution, namely, flexibility, the ability to effect swift and sudden changes of tactics if changes in objective conditions demand them, and to choose another path for the achievement of our goal if the former path proves to be inexpedient or impossible at the given moment.

Borne along on the crest of the wave of enthusiasm, rousing first the political enthusiasm and then the military enthusiasm of the people, we expected to accomplish economic tasks just as great as the political and military tasks we had accomplished by relying directly on this enthusiasm. We expected—or perhaps it would be truer to say that we presumed without having given it adequate consideration—to be able to organise the state production and the state distribution of products on communist lines in a small-peasant country directly as ordered by the proletarian state. Experience has proved that we were wrong. It appears that a number of transitional stages were necessary—state capitalism and socialism—in order to prepare—to prepare by many years of effort—for the transition to communism. Not directly relying on enthusiasm, but aided by the enthusiasm engendered by the great revolution, and on the basis of personal interest, personal incentive and business principles, we must first set to work in this small peasant country to build solid gangways to socialism by way of state capitalism. Otherwise we shall never get to communism, we shall never bring scores of millions of people to communism. That is what experience, the objective course of the development of the revolution, has taught us.

And we, who during these three or four years have learned a little to make abrupt changes of front (when abrupt changes of front are needed), have begun zealously, attentively and sedulously (although still not zealously, attentively and sedulously enough) to learn to make a new change of front, namely, the New Economic Policy. The proletarian state must become a cautious, assiduous and shrewd “businessman”, a punctilious wholesale merchant—otherwise it will never succeed in putting this small-peasant country economically on its feet. Under existing conditions, living as we are side by side with the capitalist (for the time being capitalist) West, there is no other way of progressing to communism. A wholesale merchant seems to be an economic type as remote from communism as heaven from earth. But that is one of the contradictions which, in actual life, lead from a small-peasant economy via state capitalism to socialism. Personal incentive will step up production; we must increase production first and foremost and at all costs. Wholesale trade economically unites millions of small peasants: it gives them a personal incentive, links them up and leads them to the next step, namely, to various forms of association and alliance in the process of production itself. We have already started the necessary changes in our economic policy and already have some successes to our credit; true, they are small and partial, but nonetheless they are successes. In this new field of “tuition” we are already finishing our preparatory class. By persistent and assiduous study, by making practical experience the test of every step we take, by not fearing to alter over and over again what we have already begun, by correcting our mistakes and most carefully analysing their significance, we shall pass to the higher classes. We shall go through the whole “course”, although the present state of world economics and world politics has made that course much longer and much more difficult than we would have liked. No matter at what cost, no matter how severe the hardships of the transition period may be—despite disaster, famine and ruin—we shall not flinch; we shall triumphantly carry our cause to its goal.

And we, who during these three or four years have learned a little to make abrupt changes of front (when abrupt changes of front are needed), have begun zealously, attentively and sedulously (although still not zealously, attentively and sedulously enough) to learn to make a new change of front, namely, the New Economic Policy. The proletarian state must become a cautious, assiduous and shrewd “businessman”, a punctilious wholesale merchant—otherwise it will never succeed in putting this small-peasant country economically on its feet. Under existing conditions, living as we are side by side with the capitalist (for the time being capitalist) West, there is no other way of progressing to communism. A wholesale merchant seems to be an economic type as remote from communism as heaven from earth. But that is one of the contradictions which, in actual life, lead from a small-peasant economy via state capitalism to socialism. Personal incentive will step up production; we must increase production first and foremost and at all costs. Wholesale trade economically unites millions of small peasants: it gives them a personal incentive, links them up and leads them to the next step, namely, to various forms of association and alliance in the process of production itself. We have already started the necessary changes in our economic policy and already have some successes to our credit; true, they are small and partial, but nonetheless they are successes. In this new field of “tuition” we are already finishing our preparatory class. By persistent and assiduous study, by making practical experience the test of every step we take, by not fearing to alter over and over again what we have already begun, by correcting our mistakes and most carefully analysing their significance, we shall pass to the higher classes. We shall go through the whole “course”, although the present state of world economics and world politics has made that course much longer and much more difficult than we would have liked. No matter at what cost, no matter how severe the hardships of the transition period may be—despite disaster, famine and ruin—we shall not flinch; we shall triumphantly carry our cause to its goal.

October 14, 1921

Note : The Extraordinary International Socialist Congress that sat in Basle on November 24-25, 1912, adopted a manifesto on war, which warned the peoples that an imperialist world war was imminent, showed the predatory objectives of that war and called upon the workers of all countries to make a determined stand for peace. It included a point, contributed by Lenin to the resolution of the Stuttgart Congress of 1907, that if an imperialist war broke out the socialists should utilise the economic and political crisis stemming from it to accelerate the downfall of capitalist class domination and to work for a socialist revolution.